When Pain Starts Shrinking the Circle of Life

Where many people get stuck—and what to do about it

Let me tell you about Alice. That’s not her real name, but her story is one I see often.

Alice is a runner. Running isn’t just exercise for her, it’s part of how she structures her life. Some of her closest friendships are built around it. Weekend plans, meals, and even how she unwinds fit around getting out for a run. Time with her kids often involves heading to the park or the trails. Running is woven into her routines, her habits, and her identity.

One day, something started to hurt a lot during a run…

So she did what most people would do. She took a short break. That was reasonable. Giving things a few days or a week to settle is often helpful.

Then she tried running again. It still hurt.

So she took a longer break.

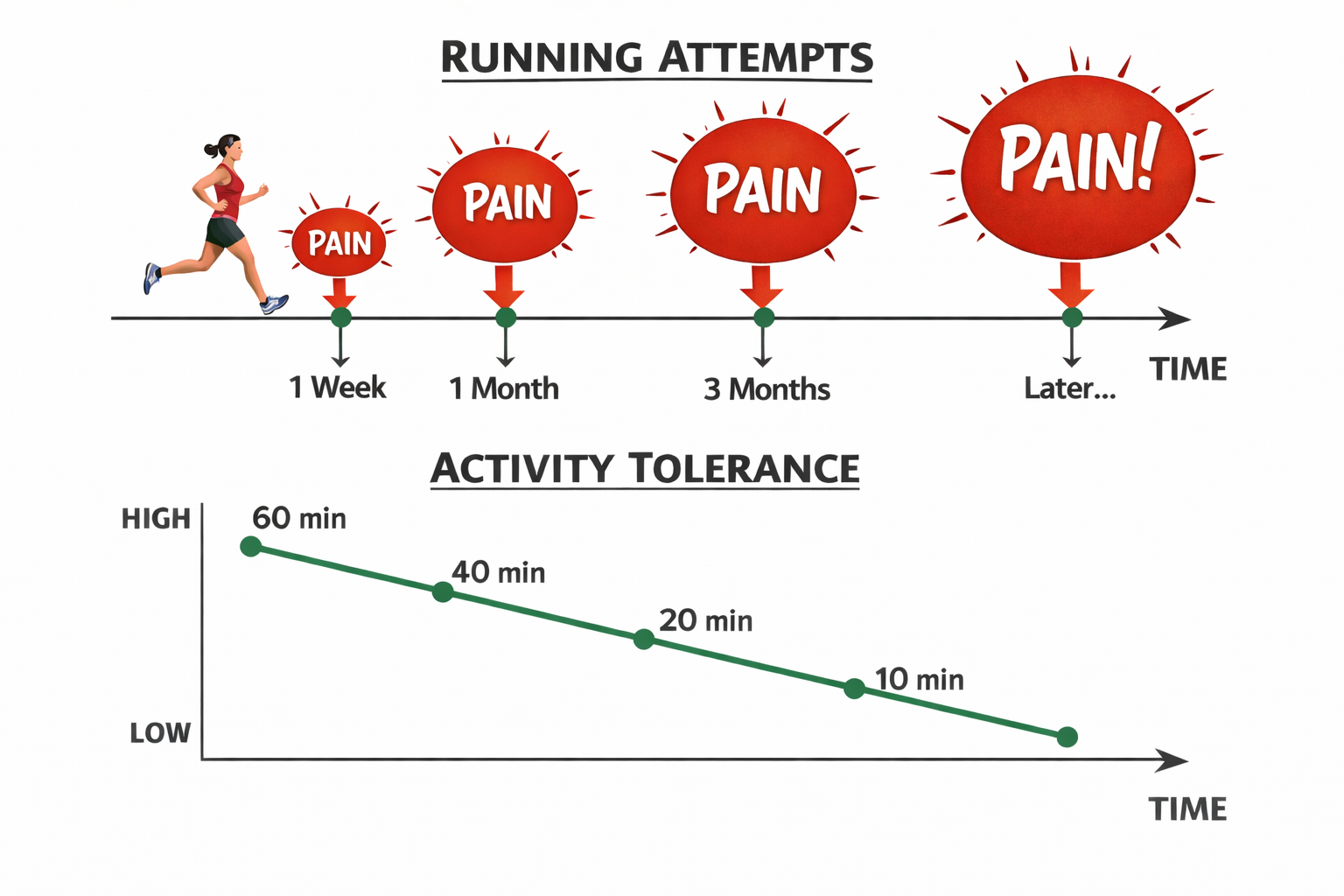

A few weeks later, she tried again… and it still hurt. Maybe even sooner than before. So she stepped away again, hoping more time would fix it.

But during that time away, something else was happening in the background. Her body was deconditioning. Strength, tolerance, and confidence were drifting down. When she came back to running, the discomfort showed up faster and lingered longer.

And then the thoughts started to creep in:

Maybe I can’t run anymore.

Maybe my body isn’t built for this.

Maybe I’m not a runner anymore.

What started as pain in her body began to affect something deeper: her confidence, her routines, and a part of her identity.

This is a place where many people get stuck.

Make it stand out

Activity avoidance leads to changes in activity tolerance over time.

Pain Has a Purpose… at First

After an injury or sudden onset of pain, it often makes sense to avoid certain movements for a short time.

The body is clearly irritated.

Tissues may be sensitive.

Protection helps things settle (yes, pain of course serves a purpose)

For many people, this phase lasts about a week or so, depending on the situation. After that, the goal usually shifts toward slowly reintroducing movement again. There is a big body of data supporting this for a variety of different injuries: back pain, ankle sprains, ACL and meniscus injuries, acute hip and knee OA flares, post-surgical rehab and so much more. The signal is clear.

Short periods of relative rest followed by a longer period of gradually getting back to all the things is key.

Where people get stuck is when avoidance continues for weeks, months or even years, instead of days.

When Pain Starts Shrinking the Circle of Life

Pain often begins in one context—running, lifting, bending, or another meaningful activity.

But when worry and avoidance build, the nervous system becomes more protective in other situations too.

People begin to:

Move more cautiously at work

Skip activities

Change routines

Avoid situations that once felt normal

Over time, pain starts to shrink the circle of life.

Activities that once felt easy begin to disappear, one by one. Sometimes they’re removed entirely. Sometimes they’re still there, but enjoyment and confidence are gone.

Pain that started in one place now seems to follow everywhere.

Why This Happens

This pattern isn’t a personal failure. It’s human nature.

Humans are wired to:

Move toward pleasant experiences

Avoid threatening or painful ones

That instinct keeps us safe.

But a response that is helpful in the short term can become unhelpful when it lasts too long.

The nervous system can become more protective, more sensitive, and more watchful, even when the original injury has settled.

Without pain, the circle fits all the things we do in our day to day. As pain persists, it can slowly take away a variety of meaningful activities. Let’s learn how to interrupt this pattern now.

Learning to Respond Differently to Sensations

Part of recovery isn’t just physical. It’s also learning how to respond when uncomfortable sensations show up. Pain, tightness, stiffness and all the rest.

One way to practice this “making space” approach is to breathe slowly and imagine a balloon gently inflating inside your body, creating more room for whatever you’re feeling. You can also soften your resistance by quietly welcoming sensations as they arise.

As you inhale, you might say:

“Welcome, pain.”

“Welcome, tightness.”

Or simply observe the sensations from a place of kindness and curiosity

Not because you enjoy the sensation, but because you’re allowing it to be present without a struggle. Sometimes, that which we resist persists.

Another important step is to reduce symptom monitoring and reassurance-seeking. When we’re anxious, it’s easy to become hyper-focused on every physical sensation, scanning the body for possible problems. As tempting as it is, this habit actually keeps anxiety and pain alive.

If you find yourself doing this, no worries, try one of these:

Name five things you can see

Notice sounds in the room

Return your focus to a task

Fully engage in a conversation

Some people also find it useful to create a short list of enjoyable or meaningful activities. When the urge to scan or worry shows up, gently redirect attention to one of those activities instead.

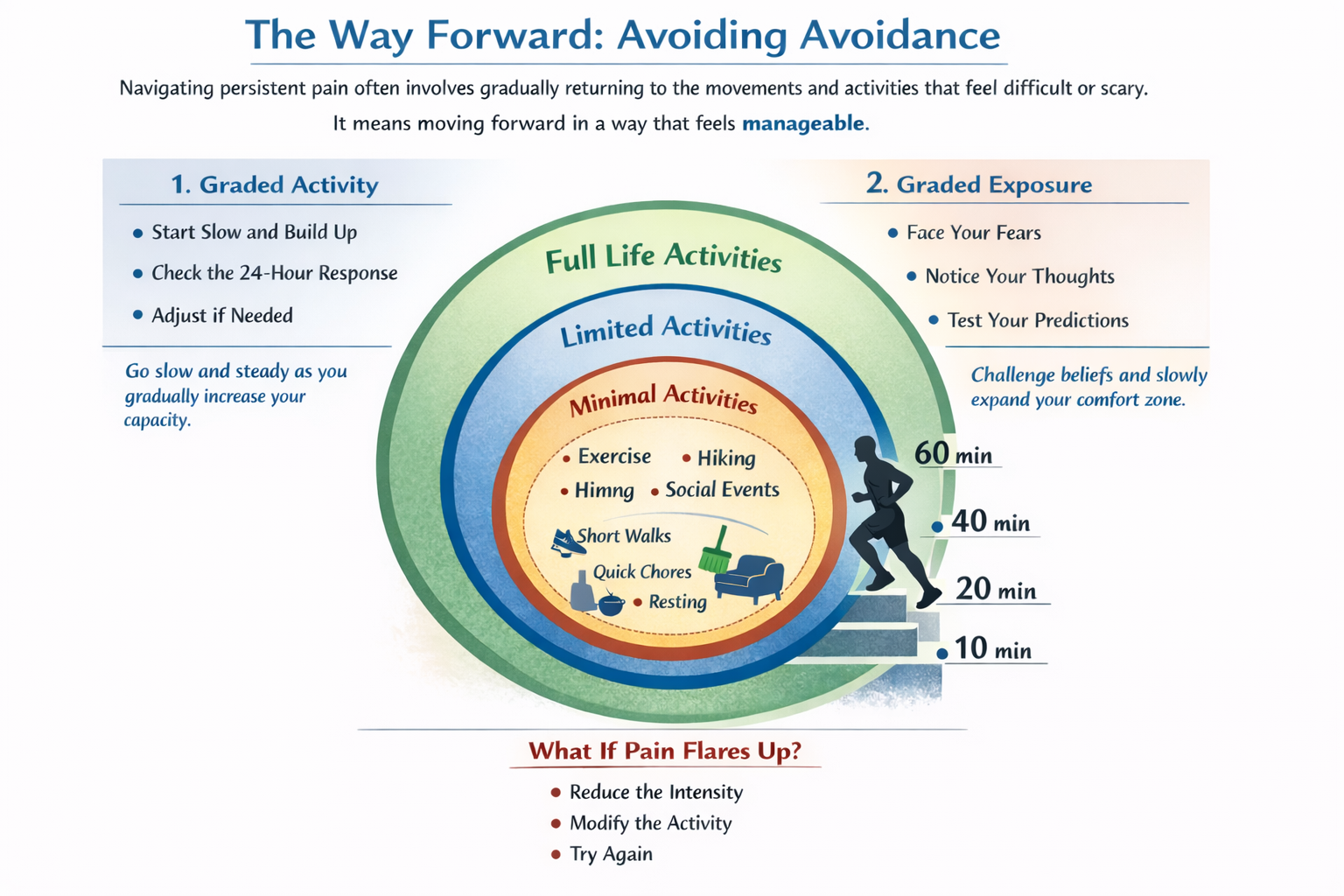

The Way Forward: Avoiding Avoidance

Navigating persistent pain often involves gradually returning to the movements and activities that feel difficult or scary.

This doesn’t mean pushing through aggressively. It means moving forward in a way that feels manageable.

Two really important ideas help guide this.

1. Graded Activity

Start with what feels doable and build slowly over time.

Use a simple rule:

How does it feel the next day?

This is sometimes called the 24-hour response:

Some soreness or discomfort is actually helpful for moving forward. We’re stimulating the areas that need attention.

If symptoms settle within 24 hours, perfect—this is what we want.

If symptoms spike and stay worse for more than 24 hours, this is tough, but you have not damaged the tissue. You have tripped the alarm.

Your next step is to adjust the activity slightly and try again.

Go slow and steady and use these as learning experiences that inform your current capacity.

2. Graded Exposure

This applies fear of movement.

If bending, lifting, or running feels scary and is something you’ve been avoiding for a while, the starting point should feel manageable.

Just as important as the movement is noticing:

What thoughts show up

What emotions appear

What story your mind is telling you

Testing Predictions

A powerful step is to form a simple hypothesis:

“If I do this movement, something bad will happen.”

Then gently test it.

Often what people discover is:

The pain is manageable

Nothing harmful happens

The body tolerates more than expected

That moment of surprise is important. It’s how the nervous system learns that something may not be as dangerous as it once believed. This is how we move forward and build more confidence.

What If Pain Flares Up?

Flare-ups can happen. That doesn’t mean damage occurred.

Instead of stopping completely:

Reduce the intensity

Modify the activity

Try again

Consistency is key. Progress usually comes from many small steps, not one big leap. Much more on pain and pain monitoring here.

Back to Alice’s Story…

Alice didn’t need a complicated program.

She didn’t need a long list of stretches, foam rolling or strengthening exercises.

What she needed was a graded running program.

She started with short, manageable intervals, running for a minute, walking for a minute. At first, it felt almost too easy. But she stuck with it and learned a lot about her current activity tolerance.

She used the 24-hour rule to guide her progress. If symptoms settled within a day, she moved forward. If they lingered beyond that, she adjusted and tried again. This wasn’t easy, but it is windy the path forward.

Week by week, her tolerance improved. But just as importantly, her confidence improved.

The pain didn’t disappear overnight, but it stopped controlling her decisions. Her circle of life began to expand again—runs with friends, weekends outside, time with her kids, the routines that made her feel like herself.

She didn’t just return to running.

She returned to her life.

The Big Picture

Pain isn’t just about tissues.

It’s also about confidence, fear, habits, and the nervous system.

Recovery often involves:

Understanding pain

Staying active in the face of discomfort and willingness to learn from the experience

Responding differently to sensations

Gradually returning to meaningful activities

The goal is to keep the circle of life as big as possible while your body adapts and improves.

Sean Overin, Registered Physiotherapist